Types Of Cancer

About Cancer

Defination of Cancer

There are many different forms of cancer. Their manifestation is a growth of cells and tissues, which differ in various aspects from the surrounding tissue. Cancers occur in all living things. All lifeforms share similar DNA and RNA blueprints and cell physiology. Therefore, the mechanisms for cancer development and methods for cancer treatment are similar.

What is Cancer?

Cancer cells are very similar to cells of the organism from which they originated and have similar (but not identical) DNA and RNA. This is the reason why they are not very often detected by the immune system, in particular if it is weakened. Cancer cells usually have an increased ability to divide rapidly and their number of divisions is not limited by telomeres on DNA (a counter system to limit number of divisions to 40-60). This can lead to the formation of large masses of tissue and in turn may lead to disruption of bodily functions due to destruction of organs or vital structures.

Anal Cancer

Anal cancer occurs in the anus, the end of the gastrointestinal tract. Anal cancer is very different from colorectal cancer, which is much more common. Anal cancer's causes, risk factors, clinical progression, staging and treatment are all very different from colorectal cancer. Anal cancer is a lump which is created by the abnormal and uncontrolled growth of cells in the anus. Anal cancer is very rare. In the UK approximately 800 patients are diagnosed annually, out of a total population of 61 million (2009).

- Sexual partner numbers - This is also linked to HPV. The more sexual partners somebody has (or has had) the higher are the chances of being infected with HPV, which is closely linked to anal cancer risk.

- Receptive anal intercourse - Both men and women who receive anal intercourse have a higher risk of developing anal cancer. HIV-positive men who have sex with men are up to 90 times more likely than the general population to develop anal cancer, this study revealed.

- Other cancers - Women who have had vaginal or cervical cancer, and men who have had penile cancer are at higher risk of developing anal cancer. This is also linked to HPV infection.

- Age - The older somebody is the higher is his/her risk of developing anal cancer. In fact, this is the case with most cancers.

- A weak immune system - People with a weakened immune system have a higher risk of developing anal cancer. This may include people with HIV/AIDS, patients who have had transplants and are taking immunosuppressant medications.

- Smoking - Smokers are significantly more likely to develop anal cancer compared to non-smokers. In fact, smoking raises the risk of developing several cancers.

- Benign anal lesions - IBD (irritable bowel disease), hemorrhoids, fistulae or cicatrices.Inflammation resulting from benign anal lesions may increase a person's risk of developing anal cancer.

- Rectal bleeding - the patient may notice blood on feces or toilet paper.

- Pain in the anal area.

- Lumps around the anus. These are frequently mistaken for piles (hemorrhoids).

- Mucus discharge from the anus.

- Jelly-like discharge from the anus.

- Anal itching.

- Change in bowel movements. This may include diarrhea, constipation, or thinning of stools.

- Fecal incontinence (problems controlling bowel movements).

- Bloating.

- Women may experience lower back pain as the tumor exerts pressure on the vagina.

- Women may experience vaginal dryness.

The type of surgery a patient will require depends on the size and position of the tumor.

- Resection - This removes a small tumor and some surrounding tissue. This type of surgery can only be carried out if the anal sphincter is not sacrificed. Patients who undergo a resection do not have their ability to pass a bowel movement affected.

- Abdominoperineal resection - the anus, rectum and a section of the bowel are surgically removed. The patient will need a colostomy - the end of the bowel is brought out onto the skin on the surface of the abdomen. A bag is placed over the stoma - the opening of the bowel - and collects the stools (feces) outside the patient's body. Although this sounds shocking, people with colostomies can lead normal lives, play sports and have active sex lives.

In most cases, the patient will probably have to undergo chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Bone Cancer

Bone cancer is a malignant (cancerous) tumor of the bone that destroys normal bone tissue (1). Not all bone tumors are malignant. In fact, benign (noncancerous) bone tumors are more common than malignant ones.

Both malignant and benign bone tumors may grow and compress healthy bone tissue, but benign tumors do not spread, do not destroy bone tissue, and are rarely a threat to life. Malignant tumors that begin in bone tissue are called primary bone cancer.

Cancer that metastasizes (spreads) to the bones from other parts of the body, such as the breast, lung, or prostate, is calledmetastatic cancer, and is named for the organ or tissue in which it began. Primary bone cancer is far less common than cancer that spreads to the bones.

- Primary bone cancer is rare. It accounts for much less than 1 percent of all cancers. About 2,300 new cases of primary bone cancer are diagnosed in the United States each year.

- Different types of bone cancer are more likely to occur in certain populations: o Osteosarcoma occurs most commonly between ages 10 and 19.

- However, people over age 40 who have other conditions, such as Paget disease (a benign condition characterized by abnormaldevelopment of new bone cells), are at increased risk of developing this cancer.

- o Chondrosarcoma occurs mainly in older adults (over age 40). The risk increases with advancing age. This disease rarely occurs in children and adolescents.

- o ESFTs occur most often in children and adolescents under 19 years of age. Boys are affected more often than girls. These tumors are extremely rare in African American children.

- Bone cancer sometimes metastasizes, particularly to the lungs, or can recur (come back), either at the same location or in other bones in the body.

- People who have had bone cancer should see their doctor regularly and should report any unusual symptoms right away.

- Follow-up varies for different types and stages of bone cancer. Generally, patients are checked frequently by their doctor and have regular blood tests and x-rays.

- People who have had bone cancer, particularly children and adolescents, have an increased likelihood of developing another type of cancer, such as leukemia, later in life.

- Regular follow-up care ensures that changes in health are discussed and that problems are treated as soon as possible.

Bladder Cancer

Your bladder is a hollow organ in the lower abdomen. It stores urine, the liquid waste made by the kidneys. Your bladder is part of the urinary tract. Urine passes from each kidney into the bladder through a long tube called a ureter. Urine leaves the bladder through a shorter tube (the urethra).

The wall of the bladder has layers of tissue:

- Inner layer: The inner layer of tissue is also called the lining. As your bladder fills up with urine, the transitional cells on the surface stretch. When you empty your bladder, these cells shrink.

- Middle layer: The middle layer is muscle tissue.When you empty your bladder, the muscle layer in the bladder wall squeezes the urine out of your body.

- Outer layer: The outer layer covers the bladder. It has fat, fibrous tissue, and blood vessels.

- Smoking : Smoking tobacco is the most important risk factor for bladder cancer. Smoking causes most of the cases of bladder cancer.People who smoke for many years have a higher risk than nonsmokers or those who smoke for a short time. How to Quit Tobacco Quitting is important for anyone who uses tobacco.

- Chemicals in the workplace : Some people have a higher risk of bladder cancer because of cancer-causing chemicals in their workplace. Workers in the dye, rubber, chemical, metal, textile, and leather industries may be at risk of bladder cancer. Also at risk are hairdressers, machinists, printers, painters, and truck drivers.

- Personal history of bladder cancer:People who have had bladder cancer have an increased risk of getting the disease again.

- Certain cancer treatments:People with cancer who have been treated with certain drugs (such ascyclophosphamide) may be at increased risk of bladder cancer. Also, people who have had radiation therapy to the abdomen or pelvis may be at increased risk.

- Arsenic : Arsenic is a poison that increases the risk of bladder cancer. In some areas of the world, arsenic may be found at high levels in drinking water. However, the United States has safety measures limiting the arsenic level in public drinking water.

- Family history of bladder cancer : People with family members who have bladder cancer have a slightly increased risk of the disease. Many people who get bladder cancer have none of these risk factors, and many people who have known risk factors develop the disease.

- Finding blood in your urine (which may make the urine look rusty or darker red)

- Feeling an urgent need to empty your bladder

- Having to empty your bladder more often than you used to

- Feeling the need to empty your bladder without results

- Needing to strain (bear down) when you empty your bladder

- Feeling pain when you empty your bladder

These symptoms may be caused by bladder cancer or by other health problems, such as an infection. People with these symptoms should tell their doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Grade

- If cancer cells are found in the tissue sample from the bladder, the pathologist studies the sample under a microscope to learn the grade of the tumor.

- The grade tells how much the tumor tissue differs from normal bladder tissue. It may suggest how fast the tumor is likely to grow.

- Tumors with higher grades tend to grow faster than those with lower grades. They are also more likely to spread. Doctors use tumor grade along with other factors to suggest treatment options.

Brain Cancer

The brain is a soft, spongy mass of tissue. It is protected by: The bones of the skull

Three thin layers of tissue (meninges) Watery fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) that flows through spaces between the meninges and through spaces (ventricles) within the brain

The brain directs the things we choose to do (like walking and talking) and the things our body does without thinking (like breathing). The brain is also in charge of our senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell), memory, emotions, and personality.

When you're told that you have a brain tumor, it's natural to wonder what may have caused your disease. But no one knows the exact causes of brain tumors. Doctors seldom know why one person develops a brain tumor and another doesn't. Researchers are studying whether people with certain risk factors are more likely than others to develop a brain tumor. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of getting a disease. Studies have found the following risk factors for brain tumors:

- Ionizing radiation : Ionizing radiation from high dose x-rays (such as radiation therapy from a large machine aimed at the head) and other sources can cause cell damage that leads to a tumor. People exposed to ionizing radiation may have an increased risk of a brain tumor, such as meningioma or glioma.

- Family history : It is rare for brain tumors to run in a family. Only a very small number of families have several members with brain tumors. Researchers are studying whether using cell phones, having had a head injury, or having been exposed to certain chemicals at work or to magnetic fields are important risk factors. Studies have not shown consistent links between these possible risk factors and brain tumors, but additional research is needed.

The symptoms of a brain tumor depend on tumor size, type, and location. Symptoms may be caused when a tumor presses on a nerve or harms a part of the brain. Also, they may be caused when a tumor blocks the fluid that flows through and around the brain, or when the brain swells because of the buildup of fluid.

These are the most common symptoms of brain tumors:

- FHeadaches (usually worse in the morning) Nausea and vomiting

- Changes in speech, vision, or hearing,Problems balancing or walking,Changes in mood, personality, or ability to concentrate

- Problems with memory Muscle jerking or twitching (seizures or convulsions)

- Numbness or tingling in the arms or legs Most often, these symptoms are not due to a brain tumor. Another health problem could cause them. If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated.

These symptoms may be caused by bladder cancer or by other health problems, such as an infection. People with these symptoms should tell their doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

People with brain tumors have several treatment options. The options are surgery, radiation therapy, andchemotherapy. Many people get a combination of treatments.

The choice of treatment depends mainly on the following:

- The type and grade of brain tumor

- Its location in the brain

- Its size

- Your age and general health

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before you begin treatment:

- What type of brain tumor do I have?

- Is it benign or malignant?

- What is the grade of the tumor?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? How can side effects be managed?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover it?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities? What is the chance that I will have to learn how to walk, speak, read, or write after treatment?

- Would a research study (clinical trial) be appropriate for me?

- Can you recommend other doctors who could give me a second opinion about my treatment options?

- How often should I have checkups?

Breast Cancer

Inside a woman's breast are 15 to 20 sections called lobes. Each lobe is made of many smaller sections calledlobules. Lobules have groups of tiny glands that can make milk. After a baby is born, a woman's breast milk flows from the lobules through thin tubes called ducts to the nipple. Fat and fibrous tissue fill the spaces between the lobules and ducts.

The breasts also contain lymph vessels. These vessels are connected to small, round masses of tissue called lymph nodes. Groups of lymph nodes are near the breast in the underarm (axilla), above the collarbone, and in the chest behind the breastbone.

When you're told that you have breast cancer, it's natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. But no one knows the exact causes of breast cancer. Doctors seldom know why one woman develops breast cancer and another doesn't.

Doctors do know that bumping, bruising, or touching the breast does not cause cancer. And breast cancer is not contagious. You can't catch it from another person.

Doctors also know that women with certain risk factors are more likely than others to develop breast cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of getting a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for breast cancer:

- Age : The chance of getting breast cancer increases as you get older. Most women are over 60 years old when they are diagnosed.

- Personal health history : Having breast cancer in one breast increases your risk of getting cancer in your other breast. Also, having certain types of abnormal breast cells (atypical hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ [LCIS], or ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]) increases the risk of invasive breast cancer. These conditions are found with a breast biopsy.

- Family health history : Your risk of breast cancer is higher if your mother, father, sister, or daughter had breast cancer. The risk is even higher if your family member had breast cancer before age 50. Having other relatives (in either your mother's or father's family) with breast cancer or ovarian cancer may also increase your risk.

- Certain genome changes : Changes in certain genes, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2, substantially increase the risk of breast cancer. Tests can sometimes show the presence of these rare, specific gene changes in families with many women who have had breast cancer, and health care providers may suggest ways to try to reduce the risk of breast cancer or to improve the detection of this disease in women who have these genetic changes.

- Reproductive and menstrual history :

- The older a woman is when she has her first child, the greater her chance of breast cancer.

- Women who never had children are at an increased risk of breast cancer.

- Women who had their first menstrual period before age 12 are at an increased risk of breast cancer.

- Women who went through menopause after age 55 are at an increased risk of breast cancer.

- Women who take menopausal hormone therapy for many years have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Early breast cancer usually doesn't cause symptoms. But as the tumor grows, it can change how the breast looks or feels.

The common changes include:

- A lump or thickening in or near the breast or in the underarm area

- A change in the size or shape of the breast

- Problems with memory Muscle jerking or twitching (seizures or convulsions)

- Dimpling or puckering in the skin of the breast

- A nipple turned inward into the breast

- Discharge (fluid) from the nipple, especially if it's bloody

- Scaly, red, or swollen skin on the breast, nipple, or areola (the dark area of skin at the center of the breast). The skin may have ridges or pitting so that it looks like the skin of an orange.

You should see your health care provider about any symptom that does not go away. Most often, these symptoms are not due to cancer. Another health problem could cause them. If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your health care provider so that the problems can be diagnosed and treated.

Women with breast cancer have many treatment options. The treatment that's best for one woman may not be best for another.

The options are surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. You may receive more than one type of treatment. The treatment options are described below.

Surgery and radiation therapy are types of local therapy. They remove or destroy cancer in the breast.

Hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy are types of systemic therapy. The drug enters the bloodstream and destroys or controls cancer throughout the body.

The treatment that's right for you depends mainly on the stage of the cancer, the results of the hormone receptor tests, the result of the HER2/neu test, and your general health. See Treatment choices by stage.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before you begin treatment:

- What did the hormone receptor tests show? What did other lab tests show? Would genetic testing be helpful to me or my family?

- Do any lymph nodes show signs of cancer?

- What is the stage of the disease? Has the cancer spread?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- What can I do to prepare for treatment?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? How can side effects be managed?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover it?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Would a research study (clinical trial) be appropriate for me?

- Can you recommend other doctors who could give me a second opinion about my treatment options?

- How often should I have checkups?

Treatment Choices by Stage

Your treatment options depend on the stage of your disease and these factors:

- The size of the tumor in relation to the size of your breast

- The results of lab tests (such as whether the breast cancer cells need hormones to grow)

- Whether you have gone through menopause

- Your general health

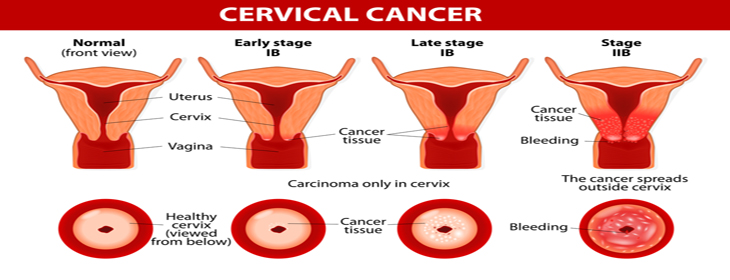

Cervix Cancer

The cervix is part of a woman's reproductive system. It's in the pelvis. The cervix is the lower, narrow part of theuterus (womb).

The cervix is a passageway:

- The cervix connects the uterus to the vagina. During a menstrual period, blood flows from the uterus through the cervix into the vagina. The vagina leads to the outside of the body.

- The cervix makes mucus. During sex, mucus helps sperm move from the vagina through the cervix into the uterus.

- During pregnancy, the cervix is tightly closed to help keep the baby inside the uterus. During childbirth, the cervix opens to allow the baby to pass through the vagina.

- When you get a diagnosis of cervical cancer, it’s natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. Doctors usually can’t explain why one woman develops cervical cancer and another doesn’t.

- However, we do know that a woman with certain risk factors may be more likely than other women to develop cervical cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

- Studies have found that infection with the virus called HPV is the cause of almost all cervical cancers. Most adults have been infected with HPV at some time in their lives, but most infections clear up on their own. An HPV infection that doesn’t go away can cause cervical cancer in some women. The NCI fact sheet HPV and Cancer has more information.

- Other risk factors, such as smoking, can act to increase the risk of cervical cancer among women infected with HPV even more. The NCI booklet Understanding Cervical Changes describes other risk factors for cervical cancer.

- A woman’s risk of cervical cancer can be reduced by getting regular cervical cancer screening tests. If abnormal cervical cell changes are found early, cancer can be prevented by removing or killing the changed cells before they become cancer cells.

- Another way a woman can reduce her risk of cervical cancer is by getting an HPV vaccine before becoming sexually active (between the ages of 9 and 26). Even women who get an HPV vaccine need regular cervical cancer screening tests.

Early cervical cancers usually don’t cause symptoms. When the cancer grows larger, women may notice abnormal vaginal bleeding:

- Bleeding that occurs between regular menstrual periods

- Bleeding after sexual intercourse, douching, or a pelvic exam

- Menstrual periods that last longer and are heavier than before

- Bleeding after going through menopause

Women may also notice…

- Increased vaginal discharge

- Pelvic pain

- Pelvic pain

- Cervical cancer, infections, or other health problems may cause these symptoms. A woman with any of these symptoms should tell her doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Treatment options for women with cervical cancer are…

- Surgery

- Radiation Therapy

- Chemotherapy

- A combination of these method

- The choice of treatment depends mainly on the size of the tumor and whether the cancer has spread. The treatment choice may also depend on whether you would like to become pregnant someday.

You may want to ask the doctor these questions before treatment begins:

- What is the stage of my disease? Has the cancer spread? If so, where?

- May I have a copy of the report from the pathologist?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Will I have more than one kind of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? What can we do to control the side effects?

- What can I do to prepare for treatment?

- Will I have to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover the cost?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- How may treatment affect my sex life?

- How often should I have checkups?

- Will I be able to get pregnant and have children after treatment? Should I preserve eggs before treatment starts?

- What can I do to take care of myself during treatment?

- What is my chance of a full recovery?

- How often will I need checkups after treatment?

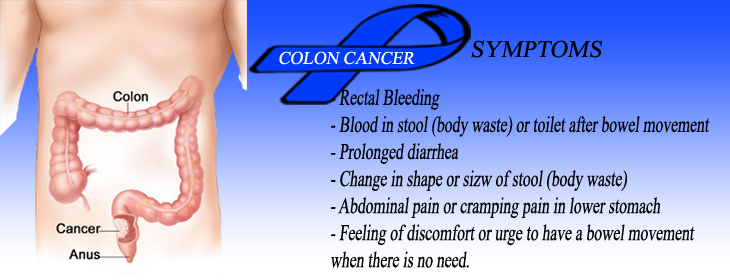

Colon and Rectum Cancer

The colon and rectum are parts of the digestive system. They form a long, muscular tube called the large intestine (also called the large bowel). The colon is the first 4 to 5 feet of the large intestine, and the rectum is the last several inches.

Partly digested food enters the colon from the small intestine. The colon removes water and nutrients from the food and turns the rest into waste (stool). The waste passes from the colon into the rectum and then out of the body through the anus.

No one knows the exact causes of colorectal cancer. Doctors often cannot explain why one person develops this disease and another does not. However, it is clear that colorectal cancer is not contagious. No one can catch this disease from another person.

Research has shown that people with certain risk factors are more likely than others to develop colorectal cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for colorectal cancer:

- Age over 50 :Colorectal cancer is more likely to occur as people get older. More than 90 percent of people with this disease are diagnosed after age 50. The average age at diagnosis is 72.

- Colorectal polyps :Polyps are growths on the inner wall of the colon or rectum. They are common in people over age 50. Most polyps are benign (not cancer), but some polyps (adenomas) can become cancer. Finding and removing polyps may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.

- Family history of colorectal cancer : Close relatives (parents, brothers, sisters, or children) of a person with a history of colorectal cancer are somewhat more likely to develop this disease themselves, especially if the relative had the cancer at a young age. If many close relatives have a history of colorectal cancer, the risk is even greater.

- DietStudies suggest that diets high in fat (especially animal fat) and low in calcium, folate, and fibermay increase the risk of colorectal cancer. Also, some studies suggest that people who eat a diet very low in fruits and vegetables may have a higher risk of colorectal cancer. However, results from diet studies do not always agree, and more research is needed to better understand how diet affects the risk of colorectal cancer.

- Having diarrhea or constipation

- Feeling that your bowel does not empty completely

- Finding blood (either bright red or very dark) in your stool

- Finding your stools are narrower than usual

- Frequently having gas pains or cramps, or feeling full or bloated

- Losing weight with no known reason

- Feeling very tired all the time

- Having nausea or vomiting

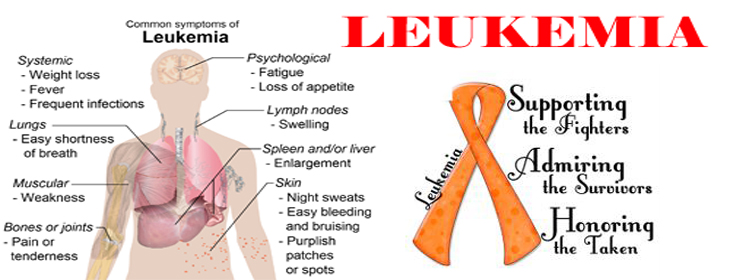

Leukemia Cancer

Leukemia is cancer that starts in the tissue that forms blood. To understand cancer, it helps to know how normal blood cells form.

Normal Blood Cells

Most blood cells develop from cells in the bone marrow called stem cells. Bone marrow is the soft material in the center of most bones. Stem cells mature into different kinds of blood cells. Each kind has a special job: White blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets are made from stem cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old or get damaged, they die, and new cells take their place.

First, a stem cell matures into either a myeloid stem cell or a lymphoid stem cell: • A myeloid stem cell matures into a myeloid blast. The blast can form a red blood cell, platelets, or one of several types of white blood cells. • A lymphoid stem cell matures into a lymphoid blast. The blast can form one of several types of white blood cells, such as B cells or T cells. The white blood cells that form from myeloid blasts are different from the white blood cells that form from lymphoid blasts.

When you're told that you have cancer, it's natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. No one knows the exact causes of leukemia. Doctors seldom know why one person gets leukemia and another doesn't. However, research shows that certain risk factors increase the chance that a person will get this disease. The risk factors may be different for the different types of leukemia:

Radiation:

People exposed to very high levels of radiation are much more likely than others to get acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, or acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Atomic bomb explosions:

Very high levels of radiation have been caused by atomic bomb explosions (such as those in Japan during World War II). People, especially children, who survive atomic bomb explosions are at increased risk of leukemia.

Radiation therapy:

Another source of exposure to high levels of radiation is medical treatment for cancer and other conditions. Radiation therapy can increase the risk of leukemia.

Diagnostic x-rays:

Dental x-rays and other diagnostic x-rays (such as CT scans) expose people to much lower levels of radiation. It's not known yet whether this low level of radiation to children or adults is linked to leukemia. Researchers are studying whether having many x-rays may increase the risk of leukemia. They are also studying whether CT scans during childhood are linked with increased risk of developing leukemia.

Smoking:

Smoking cigarettes increases the risk of acute myeloid leukemia.

Benzene:

Exposure to benzene in the workplace can cause acute myeloid leukemia. It may also cause chronic myeloid leukemia or acute lymphocytic leukemia. Benzene is used widely in the chemical industry. It's also found in cigarette smoke and gasoline.

Chemotherapy:

Cancer patients treated with certain types of cancer-fighting drugs sometimes later get acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphocytic leukemia. For example, being treated with drugs known asalkylating agents or topoisomerase inhibitors is linked with a small chance of later developing acute leukemia.

Down syndrome and certain other inherited diseases:

Down syndrome and certain other inherited diseases increase the risk of developing acute leukemia.

Myelodysplastic syndrome and certain other blood disorders:

People with certain blood disorders are at increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia.

Human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I):

People with HTLV-I infection are at increased risk of a rare type of leukemia known as adult T-cell leukemia. Although the HTLV-I virus may cause this rare disease, adult T-cell leukemia and other types of leukemia are not contagious.

Family history of leukemia:

It's rare for more than one person in a family to have leukemia. When it does happen, it's most likely to involve chronic lymphocytic leukemia. However, only a few people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia have a father, mother, brother, sister, or child who also has the disease.

Having one or more risk factors does not mean that a person will get leukemia. Most people who have risk factors never develop the disease.

Like all blood cells, leukemia cells travel through the body. The symptoms of leukemia depend on the number of leukemia cells and where these cells collect in the body.

People with chronic leukemia may not have symptoms. The doctor may find the disease during a routine blood test.

People with acute leukemia usually go to their doctor because they feel sick. If the brain is affected, they may have headaches, vomiting, confusion, loss of muscle control, or seizures. Leukemia also can affect other parts of the body such as the digestive tract, kidneys, lungs, heart, or testes.

Common symptoms of chronic or acute leukemia may include:

- Swollen lymph nodes that usually don't hurt (especially lymph nodes in the neck or armpit)

- Fevers or night sweats

- Frequent infections

- Feeling weak or tired

- Bleeding and bruising easily (bleeding gums, purplish patches in the skin, or tiny red spots under the skin)

- Swelling or discomfort in the abdomen (from a swollen spleen or liver)

- Weight loss for no known reason

- Pain in the bones or joints

Most often, these symptoms are not due to cancer. An infection or other health problems may also cause these symptoms. Only a doctor can tell for sure. Anyone with these symptoms should tell the doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Supportive Care

Leukemia and its treatment can lead to other health problems. You can have supportive care before, during, or after cancer treatment.

Supportive care is treatment to prevent or fight infections, to control pain and other symptoms, to relieve the side effects of therapy, and to help you cope with the feelings that a diagnosis of cancer can bring. You may receive supportive care to prevent or control these problems and to improve your comfort and quality of life during treatment.

Infections:

Because people with leukemia get infections very easily, you may receive antibiotics and other drugs. Some people receive vaccines against the flu and pneumonia. The health care team may advise you to stay away from crowds and from people with colds and other contagious diseases. If an infection develops, it can be serious and should be treated promptly. You may need to stay in the hospital for treatment.

Anemia and bleeding:

Anemia and bleeding are other problems that often require supportive care. You may need a transfusion of red blood cells or platelets. Transfusions help treat anemia and reduce the risk of serious bleeding.

Dental problems:

Leukemia and chemotherapy can make the mouth sensitive, easily infected, and likely to bleed. Doctors often advise patients to have a complete dental exam and, if possible, undergo needed dental care before chemotherapy begins. Dentists show patients how to keep their mouth clean and healthy during treatment.

Non Hodgkin Cancer

What Is Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma?

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Cells

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is cancer that begins in cells of the immune system. The immune system fightsinfections and other diseases. The lymphatic system is part of the immune system.

The lymphatic system includes the following:

- Lymph vessels:

- Lymph:

- Lymph nodes:

- Other parts of the lymphatic system:

The lymphatic system has a network of lymph vessels. Lymph vessels branch into all thetissues of the body.

The lymph vessels carry clear fluid called lymph. Lymph contains white blood cells, especiallylymphocytes such as B cells and T cells.

Lymph vessels are connected to small, round masses of tissue called lymph nodes. Groups of lymph nodes are found in the neck, underarms, chest, abdomen, and groin. Lymph nodes store white blood cells. They trap and remove bacteria or other harmful substances that may be in the lymph.

Other parts of the lymphatic system include the tonsils, thymus, and spleen. Lymphatic tissue is also found in other parts of the body including the stomach, skin, and small intestine. Because lymphatic tissue is in many parts of the body, lymphoma can start almost anywhere. Usually, it's first found in a lymph node.

Doctors seldom know why one person develops non-Hodgkin lymphoma and another does not. But research shows that certain risk factors increase the chance that a person will develop this disease.

In general, the risk factors for non-Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

Weakened immune system:

The risk of developing lymphoma may be increased by having a weakened immune system (such as from an inherited condition or certain drugs used after an organ transplant).

Certain infections:

Having certain types of infections increases the risk of developing lymphoma. However, lymphoma is not contagious. You cannot catch lymphoma from another person. The following are the main types of infection that can increase the risk of lymphoma: o Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): HIV is the virus that causes AIDS.

People who have HIV infection are at much greater risk of some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Age:

Although non-Hodgkin lymphoma can occur in young people, the chance of developing this disease goes up with age. Most people with non-Hodgkin lymphoma are older than 60. (For information about this disease in children, call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER.) Researchers are studying obesity and other possible risk factors for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. People who work with herbicides or certain other chemicals may be at increased risk of this disease. Researchers are also looking at a possible link between using hair dyes before 1980 and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Having one or more risk factors does not mean that a person will develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Most people who have risk factors never develop cancer.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can cause many symptoms:

- Swollen, painless lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever

- Soaking night sweats

- Coughing, trouble breathing, or chest pain

- Weakness and tiredness that don't go away

- Pain, swelling, or a feeling of fullness in the abdomen

Most often, these symptoms are not due to cancer. Infections or other health problems may also cause these symptoms. Anyone with symptoms that do not go away within 2 weeks should see a doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated.

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your needs.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist, or you may ask for a referral. Specialists who treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma include hematologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Your doctor may suggest that you choose an oncologist who specializes in the treatment of lymphoma. Often, such doctors are associated with major academic centers. Your health care team may also include an oncology nurse and a registered dietitian.

The choice of treatment depends mainly on the following:

If you have indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma without symptoms, you may not need treatment for the cancer right away. The doctor watches your health closely so that treatment can start when you begin to have symptoms. Not getting cancer treatment right away is called watchful waiting.

If you have indolent lymphoma with symptoms, you will probably receive chemotherapy and biological therapy.Radiation therapy may be used for people with Stage I or Stage II lymphoma. If you have aggressive lymphoma, the treatment is usually chemotherapy and biological therapy. Radiation therapy also may be used.

If non-Hodgkin lymphoma comes back after treatment, doctors call this a relapse or recurrence. People with lymphoma that comes back after treatment may receive high doses of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, followed by stem cell transplantation. You may want to know about side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. Because chemotherapy and radiation therapy often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them.

At any stage of the disease, you can have supportive care. Supportive care is treatment to control pain and other symptoms, to relieve the side effects of therapy, and to help you cope with the feelings that a diagnosis of cancer can bring. See the Supportive Care section. You may want to talk to your doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. See the Taking Part in Cancer Research section.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before you begin treatment:

- What type of lymphoma do I have? May I have a copy of the report from the pathologist?

- What is the stage of my disease? Where are the tumors?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

- Will I have more than one kind of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment? How will we know the treatment is working? What tests will be used to check its effectiveness? How often will I get these tests?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? What can we do to control the side effects?

- How long will treatment last?

- Will I have to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What can I do to take care of myself during treatment?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover the cost?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Would a clinical trial be right for me?

- How often will I need checkups?

Watchful Waiting

People who choose watchful waiting put off having cancer treatment until they have symptoms. Doctors sometimes suggest watchful waiting for people with indolent lymphoma. People with indolent lymphoma may not have problems that require cancer treatment for a long time. Sometimes the tumor may even shrink for a while without therapy. By putting off treatment, they can avoid the side effects of chemotherapy or radiation therapy. If you and your doctor agree that watchful waiting is a good idea, the doctor will check you regularly (every 3 months). You will receive treatment if symptoms occur or get worse.

Some people do not choose watchful waiting because they don't want to worry about having cancer that is not treated. Those who choose watchful waiting but later become worried should discuss their feelings with the doctor.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before choosing watchful waiting:

- If I choose watchful waiting, can I change my mind later on?

- Will the disease be harder to treat later?

- How often will I have checkups?

- Between checkups, what problems should I report?

Ovaries Cancer

The ovaries are part of a woman's reproductive system. They are in the pelvis. Each ovary is about the size of an almond.

The ovaries make the female hormones — estrogen and progesterone. They also release eggs. An egg travels from an ovary through a fallopian tube to the womb (uterus).

When a woman goes through her "change of life" (menopause), her ovaries stop releasing eggs and make far lower levels of hormones.

Doctors cannot always explain why one woman develops ovarian cancer and another does not. However, we do know that women with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop ovarian cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for ovarian cancer:

Family history of cancer:

Women who have a mother, daughter, or sister with ovarian cancer have an increased risk of the disease. Also, women with a family history of cancer of the breast, uterus, colon, or rectum may also have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. If several women in a family have ovarian or breast cancer, especially at a young age, this is considered a strong family history. If you have a strong family history of ovarian or breast cancer, you may wish to talk to a genetic counselor. The counselor may suggest genetic testing for you and the women in your family. Genetic tests can sometimes show the presence of specific gene changes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer.

Personal history of cancer:

Women who have had cancer of the breast, uterus, colon, or rectum have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

Age over 55:

Most women are over age 55 when diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

Never pregnant:

Older women who have never been pregnant have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Menopausal hormone therapy

Some studies have suggested that women who take estrogen by itself (estrogen without progesterone) for 10 or more years may have an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Scientists have also studied whether taking certain fertility drugs, using talcum powder, or being obese are risk factors. It is not clear whether these are risk factors, but if they are, they are not strong risk factors.

Having a risk factor does not mean that a woman will get ovarian cancer. Most women who have risk factors do not get ovarian cancer. On the other hand, women who do get the disease often have no known risk factors, except for growing older. Women who think they may be at risk of ovarian cancer should talk with their doctor.

Early ovarian cancer may not cause obvious symptoms. But, as the cancer grows, symptoms may include:

- Pressure or pain in the abdomen, pelvis, back, or legs

- A swollen or bloated abdomen

- Nausea, indigestion, gas, constipation, or diarrhea

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling the need to urinate often

- Unusual vaginal bleeding (heavy periods, or bleeding after menopause)

Feeling very tired all the time Less common symptoms include:

Most often these symptoms are not due to cancer, but only a doctor can tell for sure. Any woman with these symptoms should tell her doctor.

Supportive Care

Many women with ovarian cancer want to take an active part in making decisions about their medical care. It is natural to want to learn all you can about your disease and treatment choices. Knowing more about ovarian cancer helps many women cope.

Shock and stress after the diagnosis can make it hard to think of everything you want to ask your doctor. It often helps to make a list of questions before an appointment. To help remember what your doctor says, you may take notes or ask whether you may use a tape recorder. You may also want to have a family member or friend with you when you talk to your doctor-to take part in the discussion, to take notes, or just to listen.

You do not need to ask all your questions at once. You will have other chances to ask your doctor or nurse to explain things that are not clear and to ask for more details.

Your doctor may refer you to a gynecologic oncologist, a surgeon who specializes in treating ovarian cancer. Or you may ask for a referral. Other types of doctors who help treat women with ovarian cancer include gynecologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. You may have a team of doctors and nurses.

Getting a Second Opinion

Before starting treatment, you might want a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment plan. Many insurance companies cover a second opinion if you or your doctor requests it.

It may take some time and effort to gather medical records and arrange to see another doctor. In most cases, a brief delay in starting treatment will not make treatment less effective. To make sure, you should discuss this delay with your doctor.

Sometimes women with ovaries cancer need treatment right away. There are a number of ways to find a doctor for a second opinion:

- Your doctor may refer you to one or more specialists. At cancer centers, several specialists often work together as a team.

- NCI's Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER, can tell you about nearby treatment centers. Information Specialists also can assist you online at LiveHelp (http://www.cancer.gov/livehelp).

- A local or state medical society, a nearby hospital, or a medical school can usually provide the names of specialists.

- NCI provides a helpful fact sheet called "How To Find a Doctor or Treatment Facility If You Have Cancer."

Treatment Methods

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. Most women have surgery andchemotherapy. Rarely, radiation therapy is used.

Cancer treatment can affect cancer cells in the pelvis, in the abdomen, or throughout the body.

Local therapy:

Surgery and radiation therapy are local therapies. They remove or destroy ovarian cancer in the pelvis. When ovarian cancer has spread to other parts of the body, local therapy may be used to control the disease in those specific areas.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy:

Chemotherapy can be given directly into the abdomen and pelvis through a thin tube. The drugs destroy or control cancer in the abdomen and pelvis.

Systemic chemotherapy:

When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein, the drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy or control cancer throughout the body.

You may want to know how treatment may change your normal activities. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

Because cancer treatments often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects depend mainly on the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each woman, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them.

You may want to talk to your doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. Clinical trials are an important option for women with all stages of ovarian cancer. The section on "The Promise of Cancer Research" has more information about clinical trials.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before your treatment begins:

- What is the stage of my disease? Has the cancer spread from the ovaries? If so, to where?

- What are my treatment choices? Do you recommend intraperitoneal chemotherapy for me? Why?

- Would a clinical trial be appropriate for me?

- Will I need more than one kind of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? What can we do to control side effects? Will they go away after treatment ends?

- What can I do to prepare for treatment?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover the cost?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Will treatment cause me to go through an early menopause?

- Will I be able to get pregnant and have children after treatment?

- How often should I have checkups after treatment?

Hodgkin Leukemia Cancer

Hodgkin Lymphoma Cells Hodgkin lymphoma is a cancer that begins in cells of the immune system. The immune system fights infectionsand other diseases. The lymphatic system is part of the immune system.

The lymphatic system includes the following:

- Lymph vessels:

- Lymph:

- Lymph nodes:

- Other parts of the lymphatic system:

The lymphatic system has a network of lymph vessels. Lymph vessels branch into all thetissues of the body.

The lymph vessels carry clear fluid called lymph. Lymph contains white blood cells, especiallylymphocytes such as B cells and T cells.

Lymph vessels are connected to small, round masses of tissue called lymph nodes. Groups of lymph nodes are found in the neck, underarms, chest, abdomen, and groin. Lymph nodes store white blood cells. They trap and remove bacteria or other harmful substances that may be in the lymph.

Other parts of the lymphatic system include the tonsils, thymus, and spleen. Lymphatic tissue is also found in other parts of the body including the stomach, skin, and small intestine.

Because lymphatic tissue is in many parts of the body, Hodgkin lymphoma can start almost anywhere. Usually, it's first found in a lymph node above the diaphragm, the thin muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen. But Hodgkin lymphoma also may be found in a group of lymph nodes. Sometimes it starts in other parts of the lymphatic system.

Doctors seldom know why one person develops Hodgkin lymphoma and another does not. But research shows that certain risk factors increase the chance that a person will develop this disease.

The risk factors for Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

Certain viruses:

Having an infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may increase the risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma. However, lymphoma is not contagious. You can't catch lymphoma from another person.

Weakened immune system:

The risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma may be increased by having a weakened immune system (such as from an inherited condition or certain drugs used after an organ transplant).

Age:

Hodgkin lymphoma is most common among teens and adults aged 15 to 35 years and adults aged 55 years and older. (For information about this disease in children, call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER).

Family history:

Family members, especially brothers and sisters, of a person with Hodgkin lymphoma or other lymphomas may have an increased chance of developing this disease.

Having one or more risk factors does not mean that a person will develop Hodgkin lymphoma. Most people who have risk factors never develop cancer.

Hodgkin lymphoma can cause many symptoms:

- Swollen lymph nodes (that do not hurt) in the neck, underarms, or groin

- Becoming more sensitive to the effects of alcohol or having painful lymph nodes after drinking alcohol

- Weight loss for no known reason

- Fever that does not go away

- Soaking night sweats

- Itchy skin

- Coughing, trouble breathing, or chest pain

- Weakness and tiredness that don't go away

Most often, these symptoms are not due to cancer. Infections or other health problems may also cause these symptoms. Anyone with symptoms that last more than 2 weeks should see a doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated.

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Stem Cell Transplantation

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your needs.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist, or you may ask for a referral. Specialists who treat Hodgkin lymphoma include hematologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Your doctor may suggest that you choose an oncologist who specializes in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Often, such doctors are associated with major academic centers. Your health care team may also include an oncology nurse and aregistered dietitian.

The choice of treatment depends mainly on the following:

- The type of your Hodgkin lymphoma (most people have classical Hodgkin lymphoma)

- Its stage (where the lymphoma is found)

- Whether you have a tumor that is more than 4 inches (10 centimeters) wide

- Your age

- Whether you've had weight loss, drenching night sweats, or fevers. People with Hodgkin lymphoma may be treated with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both.

If Hodgkin lymphoma comes back after treatment, doctors call this a relapse or recurrence. People with Hodgkin lymphoma that comes back after treatment may receive high doses of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, followed by stem cell transplantation.

You may want to know about side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. Because chemotherapy and radiation therapy often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them. The younger a person is, the easier it may be to cope with treatment and its side effects.

You may want to talk to your doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. See the Taking Part in Cancer Research section.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before you begin treatment:

- What type of Hodgkin lymphoma do I have? May I have a copy of the report from the pathologist?

- What is the stage of my disease? Where are the tumors?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

- Will I have more than one kind of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? What can we do to control the side effects?

- How long will the treatment last?

- What can I do to prepare for treatment?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover the cost?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Would a clinical trial be right for me?

- How often should I have checkups after treatment?

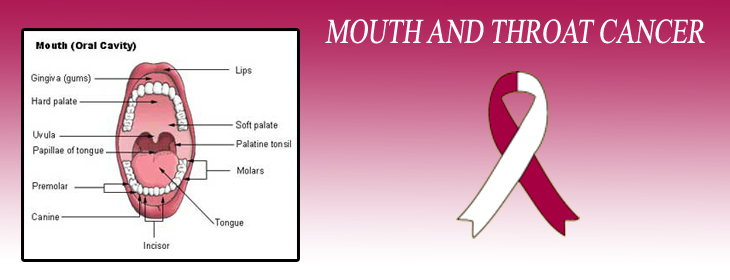

Mouth and Throat Cancer

The pictures above show the many parts of your mouth and throat:

- Lips

- Gums and Teeth

- Tongue

- Lining of your cheeks

- Salivary glands (glands that make saliva)

- Floor of your mouth (area under the tongue)

- Roof of your mouth (hard palate)

- Soft palate

- Uvula

- Oropharynx

- Tonsils

When you get a diagnosis of cancer, it's natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. Doctors can't always explain why one person gets oral cancer and another doesn't.

However, we do know that people with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop oral cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of getting a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for oral cancer:

Tobacco:

Tobacco use causes most oral cancers. Smoking cigarettes, cigars, or pipes, or using smokeless tobacco (such as snuff and chewing tobacco) causes oral cancer. The use of other tobacco products (such as bidis and kreteks) may also increase the risk of oral cancer. Heavy smokers who have smoked tobacco for a long time are most at risk for oral cancer. The risk is even higher for tobacco users who are heavy drinkers of alcohol. In fact, three out of four people with oral cancer have used tobacco, alcohol, or both. How to Quit Tobacco Quitting is important for anyone who uses tobacco. Quitting at any time is beneficial to your health. For people who already have cancer, quitting may reduce the chance of getting another cancer, lung disease, or heart disease caused by tobacco. Quitting can also help cancer treatments work better.

Heavy alcohol use:

People who are heavy drinkers are more likely to develop oral cancer than people who don't drink alcohol. The risk increases with the amount of alcohol that a person drinks. The risk increases even more if the person both drinks alcohol and uses tobacco.

HPV infection:

Some members of the HPV family of viruses can infect the mouth and throat. These viruses are passed from person to person through sexual contact. Cancer at the base of the tongue, at the back of the throat, in the tonsils, or in the soft palate is linked with HPV infection. The NCI fact sheetHuman Papillomaviruses and Cancer has more information.

Sun:

Cancer of the lip can be caused by exposure to the sun. Using a lotion or lip balm that has asunscreen can reduce the risk. Wearing a hat with a brim can also block the sun's harmful rays. The risk of cancer of the lip increases if the person also smokes.

A personal history of oral cancer:

People who have had oral cancer are at increased risk of developing another oral cancer. Smoking increases this risk.

Diet:

Some studies suggest that not eating enough fruits and vegetables may increase the chance of getting oral cancer.

Betel nut use:

Betel nut use is most common in Asia, where millions chew the product. It's a type of palm seed wrapped with a betel leaf and sometimes mixed with spices, sweeteners, and tobacco. Chewing betel nut causes oral cancer. The risk increases even more if the person also drinks alcohol and uses tobacco.

The more risk factors that a person has, the greater the chance that oral cancer will develop. However, most people with known risk factors for oral cancer don't develop the disease.

Symptoms of oral cancer may include:

- Patches inside your mouth or on your lips:

- A sore on your lip or in your mouth that doesn't heal

- Bleeding in your mouth

- Loose teeth

- Difficulty or pain when swallowing

- A lump in your neck

- An earache that doesn't go away

- Numbness of lower lip and chin

Most often, these symptoms are not from oral cancer. Another health problem can cause them. Anyone with these symptoms should tell their doctor or dentist so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Targeted Therapy

People with early oral cancer may be treated with surgery or radiation therapy. People with advanced oral cancer may have a combination of treatments. For example, radiation therapy and chemotherapy are often given at the same time. Another treatment option is targeted therapy.

The choice of treatment depends mainly on your general health, where in your mouth or throat the cancer began, the size of the tumor, and whether the cancer has spread.

Many doctors encourage people with oral cancer to consider taking part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies testing new treatments. They are an important option for people with all stages of oral cancer. See the Taking Part in Cancer Research section.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist, or you may ask for a referral. Specialists who treat oral cancer include:

- Head and neck surgeons

- Dentists who specialize in surgery of the mouth, face, and jaw (oral and maxillofacial surgeons)

- Ear, nose, and throat doctors (otolaryngologists)

- Medical oncologists

- Radiation oncologists

Other health care professionals who work with the specialists as a team may include a dentist, plastic surgeon,reconstructive surgeon, speech pathologist, oncology nurse, registered dietitian, and mental health counselor.

Your health care team can describe your treatment choices, the expected results of each, and the possible side effects. You'll want to consider how treatment may affect eating, swallowing, and talking, and whether treatment will change the way you look. You and your health care team can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your needs.

Oral cancer and its treatment can lead to other health problems. For example, radiation therapy and chemotherapy for oral cancer can cause dental problems. That's why it's important to get your mouth in good condition before cancer treatment begins. See a dentist for a thorough exam one month, if possible, before starting cancer treatment to give your mouth time to heal after needed dental work.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before your treatment begins:

- What is the stage of the disease? Has the oral cancer spread? If so, where?

- What is the goal of treatment? What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Will I have more than one type of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each type of treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? How can side effects be managed?

- Should I see a dentist before treatment begins? Can you recommend a dentist who has experience working with people who have oral cancer?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- If I have pain, how will it be controlled?

- What will the treatment cost? Will my insurance cover it?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Would a clinical trial (research study) be appropriate for me?

- How often will I need checkups?

- Can you recommend other doctors who could give me a second opinion about my treatment options?

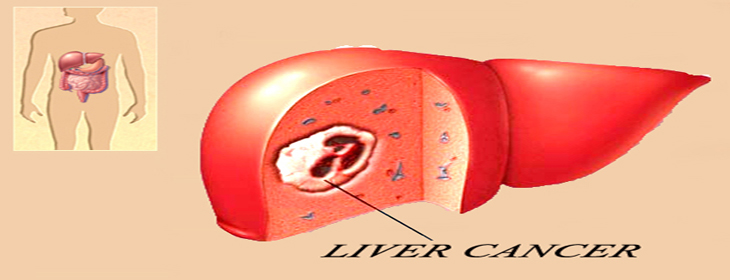

Liver Cancer

The liver is the largest organ inside your abdomen. It's found behind your ribs on the right side of your body.

The liver does important work to keep you healthy:

- It removes harmful substances from the blood.

- It makes enzymes and bile that help digest food.

- It also converts food into substances needed for life and growth.

When you get a diagnosis of cancer, it's natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. Doctors can't always explain why one person gets liver cancer and another doesn't. However, we do know that people with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop liver cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of getting a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for liver cancer:

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV):

Liver cancer can develop after many years of infection with either of these viruses. Around the world, infection with HBV or HCV is the main cause of liver cancer.

HBV and HCV can be passed from person to person through blood (such as by sharing needles) or sexual contact. An infant may catch these viruses from an infected mother. Although HBV and HCV infections are contagious diseases, liver cancer is not. You can't catch liver cancer from another person.

HBV and HCV infections may not cause symptoms, but blood tests can show whether either virus is present. If so, the doctor may suggest treatment. Also, the doctor may discuss ways to avoid infecting other people. In people who are not already infected with HBV, hepatitis B vaccine can prevent HBV infection. Researchers are working to develop a vaccine to prevent HCV infection.

Heavy alcohol use:

Having more than two drinks of alcohol each day for many years increases the risk of liver cancer and certain other cancers. The risk increases with the amount of alcohol that a person drinks.

Aflatoxin:

Liver cancer can be caused by aflatoxin, a harmful substance made by certain types of mold. Aflatoxin can form on peanuts, corn, and other nuts and grains. In parts of Asia and Africa, levels of aflatoxin are high. However, the United States has safety measures limiting aflatoxin in the food supply.

Iron storage disease:

Liver cancer may develop among people with a disease that causes the body to store too much iron in the liver and other organs.

Cirrhosis:

Cirrhosis is a serious disease that develops when liver cells are damaged and replaced with scar tissue. Many exposures cause cirrhosis, including HBV or HCV infection, heavy alcohol use, too much iron stored in the liver, certain drugs, and certain parasites. Almost all cases of liver cancer in the United States occur in people who first had cirrhosis, usually resulting from hepatitis B or C infection, or from heavy alcohol use.

Obesity and diabetes:

Studies have shown that obesity and diabetes may be important risk factors for liver cancer. The more risk factors a person has, the greater the chance that liver cancer will develop. However, many people with known risk factors for liver cancer don't develop the disease.

Early liver cancer often doesn't cause symptoms. When the cancer grows larger, people may notice one or more of these common symptoms

- Pain in the upper abdomen on the right side

- A lump or a feeling of heaviness in the upper abdomen

- Swollen abdomen (bloating)

- Loss of appetite and feelings of fullness

- Weight loss

- Weakness or feeling very tired

- Nausea and vomiting

- Yellow skin and eyes, pale stools, and dark urine from jaundice

- Fever

These symptoms may be caused by liver cancer or other health problems. If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Treatment options for people with liver cancer are surgery (including a liver transplant), ablation, embolization,targeted therapy, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. You may have a combination of treatments.

The treatment that's right for you depends mainly on the following:

- the number, size, and location of tumors in your liver

- how well your liver is working and whether you have cirrhosis

- hether the cancer has spread outside your liver

Other factors to consider include your age, general health, and concerns about the treatments and their possible side effects.

At this time, liver cancer can be cured only when it's found at an early stage (before it has spread) and only if people are healthy enough to have surgery. For people who can't have surgery, other treatments may be able to help them live longer and feel better. Many doctors encourage people with liver cancer to consider taking part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies testing new treatments. They are an important option for people with all stages of liver cancer. See the Taking Part in Cancer Research section.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist, or you may ask for a referral. Specialists who treat liver cancer include surgeons (especially hepatobiliary surgeons, surgical oncologists, and transplant surgeons), gastroenterologists,medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Your health care team may also include an oncology nurse and aregistered dietitian.

Your health care team can describe your treatment choices, the expected results of each, and the possible side effects. Because cancer therapy often damages healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Before treatment starts, ask your health care team about possible side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. You and your health care team can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your needs.

Lung Cancer

Your lungs are a pair of large organs in your chest. They are part of your respiratory system. Air enters your body through your nose or mouth. It passes through your windpipe (trachea) and through each bronchus, and goes into your lungs.

When you breathe in, your lungs expand with air. This is how your body gets oxygen.

When you breathe out, air goes out of your lungs. This is how your body gets rid of carbon dioxide.

Your right lung has three parts (lobes). Your left lung is smaller and has two lobes.

A thin tissue (the pleura) covers the lungs and lines the inside of the chest. Between the two layers of the pleura is a very small amount of fluid (pleural fluid). Normally, this fluid does not build up.

Doctors cannot always explain why one person develops lung cancer and another does not. However, we do know that a person with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop lung cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for lung cancer:

Tobacco smoke:

Tobacco smoke causes most cases of lung cancer. It's by far the most important risk factor for lung cancer. Harmful substances in smoke damage lung cells. That's why smoking cigarettes, pipes, or cigars can cause lung cancer and why secondhand smoke can cause lung cancer in nonsmokers. The more a person is exposed to smoke, the greater the risk of lung cancer. For more information, see the NCI fact sheets Harms of Smoking and Health Benefits of Quitting and Secondhand Smoke and Cancer.

Radon:

Radon is a radioactive gas that you cannot see, smell, or taste. It forms in soil and rocks. People who work in mines may be exposed to radon. In some parts of the country, radon is found in houses. Radon damages lung cells, and people exposed to radon are at increased risk of lung cancer. The risk of lung cancer from radon is even higher for smokers. For more information, see the NCI fact sheet Radon and Cancer.

Asbestos and other substances:

People who have certain jobs (such as those who work in the construction and chemical industries) have an increased risk of lung cancer. Exposure to asbestos, arsenic, chromium, nickel, soot, tar, and other substances can cause lung cancer. The risk is highest for those with years of exposure. The risk of lung cancer from these substances is even higher for smokers.

Air pollution:

Air pollution may slightly increase the risk of lung cancer. The risk from air pollution is higher for smokers.

Family history of lung cancer:

People with a father, mother, brother, or sister who had lung cancer may be at slightly increased risk of the disease, even if they don't smoke.

Personal history of lung cancer:

People who have had lung cancer are at increased risk of developing a second lung tumor.

Age over 65:

Most people are older than 65 years when diagnosed with lung cancer.

Researchers have studied other possible risk factors. For example, having certain lung diseases (such astuberculosis or bronchitis) for many years may increase the risk of lung cancer. It's not yet clear whether having certain lung diseases is a risk factor for lung cancer.

People who think they may be at risk for developing lung cancer should talk to their doctor. The doctor may be able to suggest ways to reduce their risk and can plan an appropriate schedule for checkups. For people who have been treated for lung cancer, it's important to have checkups after treatment. The lung tumor may come back after treatment, or another lung tumor may develop.

How To Quit Smoking

Quitting is important for anyone who smokes tobacco -- even people who have smoked for many years. For people who already have cancer, quitting may reduce the chance of getting another cancer. Quitting also can help cancer treatments work better.

There are many ways to get help:

- Ask your doctor about medicine or nicotine replacement therapy, such as a patch, gum, lozenge, nasal spray, or inhaler. Your doctor can suggest a number of treatments that help people quit.

- Ask your doctor to help you find local programs or trained professionals who help people stop using tobacco.

Early lung cancer often does not cause symptoms. But as the cancer grows, common symptoms may include:

- A cough that gets worse or does not go away

- breathing trouble, such as shortness of breath

- constant chest pain

- coughing up blood

- a hoarse voice

- frequent lung infections, such as pneumonia

- feeling very tired all the time

- weight loss with no known cause

Most often these symptoms are not due to cancer. Other health problems can cause some of these symptoms. Anyone with such symptoms should see a doctor to be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist who has experience treating lung cancer, or you may ask for a referral. You may have a team of specialists. Specialists who treat lung cancer include thoracic (chest) surgeons,thoracic surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Your health care team may also include a pulmonologist (a lung specialist), a respiratory therapist, an oncology nurse, and a registered dietitian.

Lung cancer is hard to control with current treatments. For that reason, many doctors encourage patients with this disease to consider taking part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are an important option for people with all stages of lung cancer. See "The Promise of Cancer Research."

The choice of treatment depends mainly on the type of lung cancer and its stage. People with lung cancer may have surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy, or a combination of treatments.

People with limited stage small cell lung cancer usually have radiation therapy and chemotherapy. For a very small lung tumor, a person may have surgery and chemotherapy. Most people with extensive stage small cell lung cancer are treated with chemotherapy only.

People with non-small cell lung cancer may have surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of treatments. The treatment choices are different for each stage. Some people with advanced cancer receive targeted therapy.

Cancer treatment is either local therapy or systemic therapy:

Local therapy:

Surgery and radiation therapy are local therapies. They remove or destroy cancer in the chest. When lung cancer has spread to other parts of the body, local therapy may be used to control the disease in those specific areas. For example, lung cancer that spreads to the brain may be controlled with radiation therapy to the head.

Systemic therapy:

Chemotherapy and targeted therapy are systemic therapies. The drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy or control cancer throughout the body.

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. You may want to know about side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. Because cancer treatments often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects depend mainly on the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them.

You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before your treatment begins: